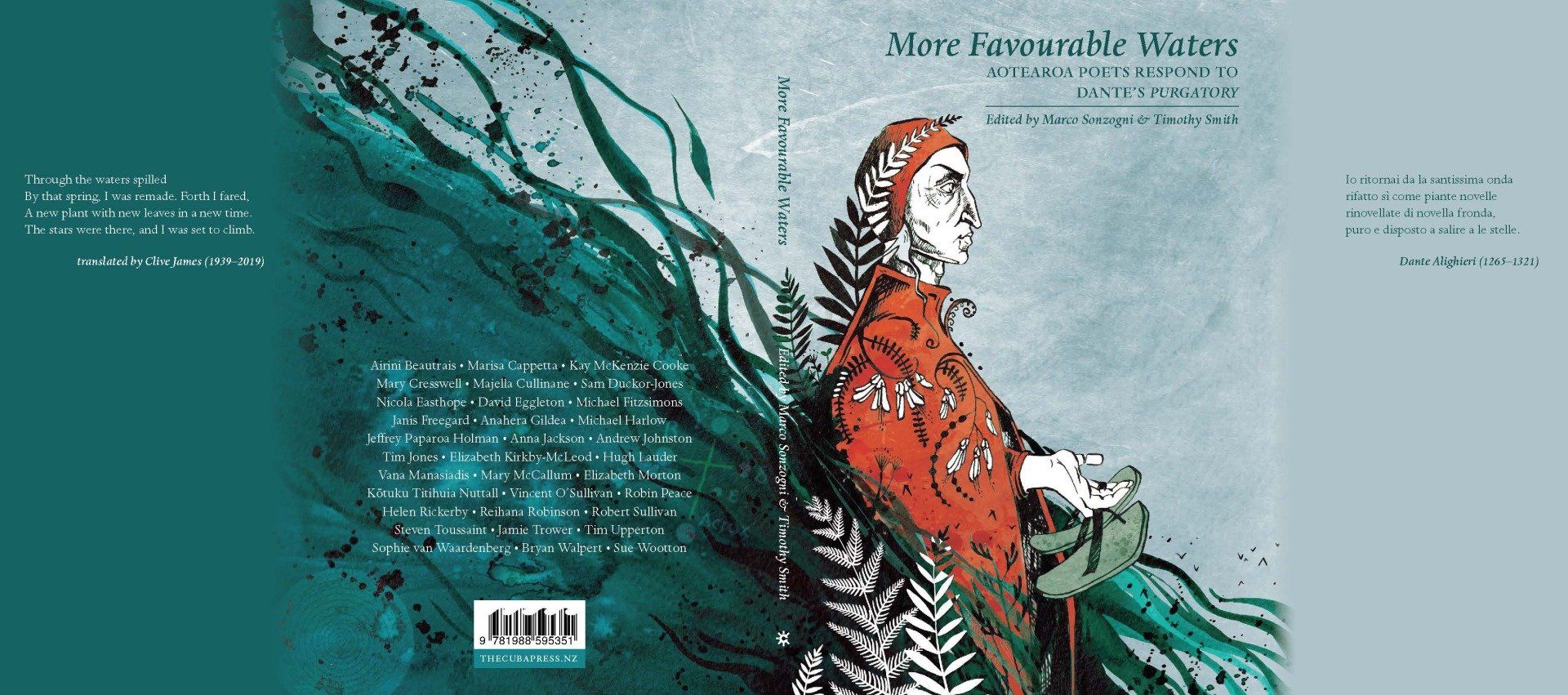

Through the waters spilled

By that spring, I was remade. Forth I fared,

A new plant with new leaves in a new time.

The stars were there, and I was set to climb.

Dante Alighieri,

Purgatory XXXII 163-66,

translated by Clive James

On 25 March 2020, New Zealanders went into lockdown, a descent into mental and physical unknowns caused by a virulent virus set on world domination. On the same day in 1300, a 35-year-old Italian, Dante Alighieri (1265–1321), began his own lockdown of sorts: private, public, poetic.

As his home city of Florence was consumed by internal issues, pilgrims from all corners of Italy and Europe were flocking to Rome (a tradition that continues) to visit the tomb of Saint Peter and earn themselves a jubilee or plenary indulgence: a spiritual vaccination, as it were, against the virus of sin and consequent temporal punishment.

The Pope of the time, Boniface VIII, had made jubilees church doctrine, translating popular pity into political power – an astute move that leveraged spiritual unity to bring about theocratic control of earthly matters. The story of course is much more complex than this and so it is best left as another story for another day.

A righteous citizen and respected intellectual, Dante wrote in Latin and in vernacular, was competent in the humanities and the sciences, and committed to poetry as much as to politics. When a poisonous cocktail of individual and collective upheavals left him an exile under a death sentence, his principles and his poetry remained his personal and professional certainties.

Locked out of his city and above all locked out of his true self, the peregrine-poet Dante embarked on a journey of redemption where he experienced the lowest lows of Hell, the middle medley of Purgatory, and the highest highs of Heaven – poised between the real and allegorical meanings of his worldly and otherworldly ordeals and struggling to keep his verse aligned with his vision.

The

Divine Comedy is the account of that journey and is to this day one of the most accomplished and influential works of literature of all time. Dante’s medieval masterpiece remains an unsurpassed example of how form and content can combine to generate timely yet timeless literature, in aesthetic as well as ethical terms. Over the centuries and across cultures, Dante’s trilogy written in the three-lined stanzas known as

terza rima has been an uncompromising invitation to zoom in on oneself and find the honesty of mind, integrity of conscience and strength of character each and every one of us must find in order to become a better person and contribute to making the world a better place.

This is why words, characters and stories from Dante’s

Divine Comedy keep finding their way into literature, art, film, music – helping humans to understand and unfold their humanity, for better and for worse. After all, from the very beginning of civilisation literary communication, oral and written, has enabled individuals and groups to witness the ups and downs of life, leaving contemporary and future audiences with enlightening and inspiring examples of how to survive, cope with, overcome and celebrate what life throws at us. And there is no doubt Dante stands out as one such enduring example –as the Latin saying goes,

nomen omen, one’s destiny is one’s name: indeed, Dante is the shortened form of

Durante, ‘lasting’.

Asked to choose the best book of the past thousand years, George Steiner, one of the most influential literary critics of our time, named the

Divine Comedy, arguing how “Dante’s totality of poetic form and philosophic thought, of ‘local universality’ and language, remains unrivalled”. Writing about giants in the arts, Umberto Eco, himself a giant of literary criticism, maintained that “in order to transform a work into a cult object, you must be able to take it to pieces, disassemble it, and unhinge it in such a way that only parts of it are remembered, regardless of their original relationship with the whole”. For “whatever is given”, as the Irish poet and Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney mused, “can always be reimagined”.

More Favourable Waters

(The Cuba Press, 2021), an anthology I have co-edited with my colleague Timothy Smith, in which Aotearoa New Zealand poets write a poem inspired by, and using verbatim, lines from Dante’s Purgatory, and my book

Quantum of Dante

(Beatnik Publishing, 2021), where the ant in Dante turns his word-hill into an ant-hill, both reimagine the Divine Comedy.

When Dante finally comes out of Hell’s lockdown to see the stars again, he finds himself Down Under, admiring the four stars of the Southern Cross and a-swim in the more favourable waters of the southern hemisphere. In Dante’s imagination, Purgatory is a (painfully slow) mountainous path to Heaven at the antipodes of Jerusalem. Tunnel through the ground beneath modern Jerusalem and you would end up in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. The closest landforms are the southern-most islands of French Polynesia, quite some distance from Aotearoa - Rapa Iti being the only populated land near this earthly Eden.

New Zealand is not exactly what Dante had in mind when he plonked his Purgatory in the middle of an ocean unseen by the people of Western Europe in the fourteenth century. Still, it is close enough for us to choose Middle Earth as the imagined setting of the middle book in Dante’s trilogy – “a setting for something to take place in” and “a place to go on from”, as poet Iain Lonie (1932–1988) put it, ending title poem and book

The Entrance to Purgatory (1986). So down under we went to Aotearoa for its more favourable waters and purgatorial mountain. And for its poetry. Dante chose a poet, Virgil, to go through the nine circles of Hell with.

We have chosen 33 poets to help him climb the seven levels of Purgatory, pairing each with a passage from a canto in Purgatory and asking them to write a poem that responds to, and includes, the assigned passage.

More Favourable Waters therefore continues in the tradition of translating Dante into our own age, place, circumstances and stories – and, of course, the people inhabiting them and narrating them. Not only is this anthology an original tribute to one of the greatest poets of all time, it also bears witness to the ongoing attraction of Dante to contemporary poets as well as the variety – ethnic, cultural, linguistic, stylistic – that enriches and distinguishes poetry in Aotearoa.

When we approached the poets, we had no idea what the reaction would be. Most replied straight away, deeply excited about being part of the project; some accepted who said they usually turned down such proposals but couldn’t resist; and many had knowledge of the poet and his work. Only one poet turned it down, citing lack of knowledge of Dante’s work, and another accepted and then bailed when they couldn’t kindle the spark that had initially ignited.

Steven Toussaint, whose powerful poem “Hillside” (Canto I) opens the anthology, emailed: “Dante and the Purgatorio in particular have been very important to my spiritual and poetic life for many years.”

Jeffrey Paparoa Holman, author of “Last exit to Purgatory” (Canto VIII), was

“honoured to honour the great man, having read my way through the Inferno for a course at City Lit in London during the 1990s”

and told us he’d visited Ravenna and the poet’s tomb.

Vincent O’Sullivan’s readiness “to have a shot at the Dante”

has gifted the anthology the 11 elegiac tercets of “Dante gifts McCahon the Southern Cross” (Canto XXIII). Anna Jackson – who wrote her own version of the Divine Comedy

in her first poetry collection, The Long Road to Teatime

(2000) – said, “I would absolutely love to take part in this”, and has also written 11 mesmerising tercets, “When we had all spoken” (Canto XXIV).

Reihana Robinson

found the invitation “intriguing” and, as her ekphrastic poem “The triumph of death” (Canto XII) demonstrates, she has “grasp[ed] the challenge with hands and heart”. For Vana Manasiadis, this was a “dream project” and her response to the invitation was as many yesses as there are cantos in the Divine Comedy – “sì, cento volte sì”

– and a poem that meditates on “negative forms of happiness” (Canto XXI) translanguaging from Greek to English to Arabic, something Dante would have enjoyed and endorsed.

The bruising anger of “Terrace of wrath” (Canto XVI) reflects how profoundly Airini Beautrais

has engaged with Dante. As did Helen Rickerby, who has been “learning Italian for quite a few years” (promising to one day read Dante in the original) and has acutely written about “all sorts of sensations” we feel inside us “when we fall in love”

(Canto III).

Kōtuku Nuttall

was “very, very interested”

and her poem, “Sophrosyne” (Canto XXII), enters Dante’s world via the world of the Classics she, like Dante, has studied. Tim Jones

– already familiar with Purgatorio

having red Mark Musa’s translation – was “ready for the challenge”, despite the middle book being “the toughest sledding of the three volumes”, and his poem, “O man” (Canto V), vividly shows it. “How to remember, how to forget” (Canto XIII) and “Assorted Loves” (Canto XVIII) prove how eagerly and warmly Elizabeth Kirkby-McLeod

and Michael Fitzsimons

have welcomed Dante – and God – into their imaginations.

David Eggleton

and Robert Sullivan

were “very keen”

and “very happy”

to be inspired by Dante: “Beatrice” (Canto IX) and “Pāua canticle” (Canto XXXIII) could not be more different as poems and yet more similar as homages to the great Italian poet. And that’s only some of the 33 Aotearoa poets who have taken on the Dante challenge.

If Team NZ has kept the Auld Mug in Aotearoa New Zealand, Team Poetry NZ are keeping the Auld Dante alive 700 years after his death.