Shirley Hazzard was an author admired for the self-reflectiveness, delicacy of phrasing, wit and irony, intensely personal resonance and finely realised sense of place which characterised both her fictional and non-fictional writings. Italy played a fundamental part in her life and work. Her first year there, 1956, was spent in Tuscany where she established a close friendship with the Vivante family, artists, philosophers, and writers, and developed the penetrating eye into social relationships of love and loss analysed in her novels set in Italy and elsewhere. She returned regularly to Naples and to Capri for the rest of her life and was made an honorary citizen of Capri in 2000. She often underlined her debt to Italy: "Frm the first day [in Naples], everything changed. I was restored to life and power and thought." The point was never simply personal but rather bound to the persistence of humanist art and thought there: "In Italy, the mysteries remain important: the accidental quality of existence, the poetry of memory, the impassioned life that is animated by awareness of eventual death. There is still synthesis, rathern than formula. There is still expressive language."

Shirley Hazzard (Sydney 1931 – New York 2016)

From the first day [in Naples], everything changed. I was restored to life and power and thought.

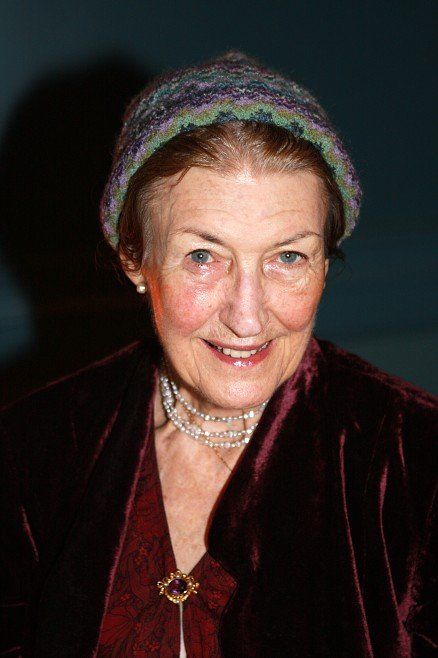

Shirley Hazzard at the Mercantile Library Center for Fiction's Annual Benefit and Awards Dinner, held at the New York Tennis and Racquet Club, 350 Park Avenue, New York, October 29, 2007. Photo Christopher Peterson.

All her four novels – The Evening of the Holiday (1966), The Bay of Noon (1970), The Transit of Venus (1980), The Great Fire (2003, which won the Miles Franklin and US National Book awards) – take readers into complex moral territory where the certainties and compulsions of sexual and romantic love are tested by individual vulnerability. Also important throughout her work have been what she called “public themes”: the human matter of political and social life, played out against a global and historical backdrop. Even among the significant cohort of Australian writers who have lived and worked in the US, Hazzard occupied a unique position, particularly in the way her work, and her position as writer, remained unconfined by national borders and paradigms.

She was born on January 30 1931 in Sydney, the younger daughter of Reginald Hazzard and Catherine Stein Hazzard who met while both were working for the firm that built the Sydney Harbour Bridge. She attended Queenwood School in Balmoral but never went to university. During the war, with fears of a Japanese invasion of Sydney running high, her school was evacuated to the rural outskirts of Sydney, as dramatised in the Australian sections of The Transit of Venus . She later observed that encountering Italian prisoners of war there was a defining moment in her humanistic education, informing her sense of the shape and scope of the world and of important human connections to be made beyond national borders: “In Australia, in wartime, Italy and Italians were a theme of derision to us — yet here were these prisoners, recognisable in simple human terms.” Also central to her world and her developing world view was literature and reading: “In childhood, I lived much in books, and imagination, where one discovers affinities.”

Immediately after the war the Hazzard family left Sydney, first for Hong Kong, then via Wellington, New Zealand, to New York, where her father took up the position of Australian trade commissioner in 1950. Hazzard never returned to Australia to live. She later described this early experience of expatriation as “fortunate, formative”, and noted that she felt it was “a privilege — to be at home in more than one place”. She found employment working in a junior capacity for the UN until the early 1960s when she left to pursue writing full time. She had begun writing while employed by the UN and her work was quickly accepted by The New Yorker. Fiction editor William Maxwell once observed that her early stories were received with some astonishment for they required almost no revision or editorial work, appearing to be “the work of a finished literary artist about whom we knew nothing whatever”.

In January 1963 Hazzard met the man who would become her husband, the eminent Flaubert translator and biographer Francis Steegmuller, 24 years her senior, at a party given by their mutual friend, novelist Muriel Spark. Hazzard described the meeting as if a scene from one of her novels: “I noticed Francis, whom I’d never met, as he entered the room. He was, and is, very tall; he was very serious, even austere; and he was wearing a fawn-coloured great coat, a sort of British Warm … It was a singular moment: colpo di fulmine — a lightning bolt. In any case we sat down in a corner together and stayed there. When we came out of that corner, you might say, we went and got married.” Hazzard and Steegmuller shared a 17 th floor apartment in the Upper East Side of Manhattan and apartments in Naples and on Capri until Steegmuller’s death in 1994 at the age of 88. They had no children.

The intensity of their shared literary life was described by a translator friend as a “conjugal version of literary high life”. The couple was intricately connected to literary and intellectual circles in New York and Italy, and also maintained friendships and correspondence for many years with several Australian authors, including Patrick White, David Malouf and Elizabeth Harrower. These literary circles might be seen as her truest affiliation, supplanting those of national belonging or connection. In 1976 Hazzard returned to Australia as a guest of the Adelaide Writers Festival and found a country transformed from the provincial place of her memory: “It was as if the country had grown younger.” Her 1977 “Letter From Australia”, commissioned by The New Yorker , provided a lengthy and optimistic account of dramatic changes in Australian society and culture in the wake of the 1972 election of the first postwar Labor government. For the story she interviewed distinctive figures of the period, including Gough Whitlam, Sydney green bans organiser Jack Mundey, South Australian premier Don Dunstan, and Tasmanian wilderness photographer and activist Olegas Truchanas. A few years later, however, when she returned again to present the 1984 ABC Boyer Lectures, she focused more heavily on the provincialism of prewar Australia. As with her later satirical representation of midcentury Australian expatriates in Japan in The Great Fire , the lectures sparked an indignant response from many commentators who felt that her representation of the country of her birth had lost touch with its contemporary culture and society.

Hazzard’s writing, both fiction and nonfiction, is defined by its dense alignment of public and private worlds, of politics and poetry and love. There is no sense in her work that these worlds are anything other than deeply and intimately interconnected, finding their expression in individual thought and action. This has been the bedrock of Hazzard’s ethical stance as writer and citizen: “There is no such thing as official cowardice. All cowardice, like true courage, is personal.” Her work began always from the premise of internationalism: in this she exemplified the idealism of the midcentury and the shared conviction that the conflagrations of global war might be balanced by a political engagement and processes for establishing international relationships. Of her decade of employment at the UN she later observed: “I was 20 and I was part of that feeling of hope that came into the world with the end of the war. I went, like many other people then, to apply to the United Nations in a spirit of idealism, little dreaming indeed that idealism was the last thing that was wanted there.”

Alongside her acclaimed fiction she published a series of essays and two books setting out her objections to UN practice and policy. She argued that from its inception the UN had been the puppet of its member governments, most particularly and perniciously the US and Soviet Union, and cited Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s depiction of the institution as “a United Governments Organisation”. These failings led to what she saw as a catastrophic capitulation on the part of the UN to McCarthyist investigations in its earliest years through the surveillance of employees who were US citizens, and later to its collusive role in the concealment of secretary-general Kurt Waldheim’s wartime involvement with the Austrian Nazi party. She was the first writer to air these stories publicly, devoting years of her writing life to that task. She also worked tirelessly behind the scenes to bring to world attention what she saw as the censorship of Solzhenitsyn’s books when they were removed from bookshops on UN territory in Geneva in 1974 at the behest of the Soviet government. She presented these labours through the figure of the citizen poet, drawing on an essay attacking corruption in the church by the poet Milton, to highlight the conflict inherent in a writer’s public conscience and sense of civic responsibility. This sense of public obligation and accountability were also informed by her commitment to the traditions of humanism in Western thought and its capacity to bring personal and political spheres into alignment: “Humanism set the dignity and singularity of a man or woman above abstractions and inventions. Through generations of the world’s fratricidal convulsions, it supplied the fragile continuity of individual civilisation. It offered hospitality to thought and art.” Although her novels remain beguilingly out of step with contemporary fiction in their style and scope and subject matter, they orient readers towards what she saw as the heart of the writer’s but also the reader’s obligation: our “responsibility to the accurate word”.

This is a lightly reworked version of the obituary which appeared in The Australian in December 2016. For further discussion of Hazzard’s work see Brigitta Olubas, Shirley Hazzard: Literary Expatriate and Cosmopolitan Humanist (Cambria Press, 2012) and Brigitta Olubas (ed), We Need Silence to Find Out What We Think. Selected Essays by Shirley Hazzard (Columbia University Press, 2016).