The emblem of the Accademia della Crusca, a frullone (sifter) with the motto "il più bel fior ne coglie", derived from Petrarca's 'Canzoniere', LXXIII, 36.

The Accademia della Crusca and the 'Settimana della lingua italiana nel mondo'

Professor John Kinder, Australia's only Corresponding Member of the illustrious and venerable Accademia della Crusca, explains the origins of the 'Settimana della lingua italiana nel mondo' celebrated this last week.

“L’italiano tra parola e immagine: graffiti, illustrazioni, fumetti”. This is the theme of the twentieth Settimana della Lingua Italiana nel Mondo, an invitation to look beyond text – spoken or written – and examine the multiple and fascinating ways in which word and image intertwine during Italy’s long linguistic history.

The Settimana della Lingua Italiana was an initiative, in 2000, of the

Accademia della Crusca, Italy’s language academy founded in Florence in 1583. It was quickly adopted by the Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale and is now celebrated in over 100 countries.

Like many other activities, the Settimana is eloquent expression of the new direction the Crusca set for itself in the second half of the twentieth century. When the fifth edition of its monumental dictionary was abandoned in 1923 – at the word ozono, but the handwritten notes for letters P-Z are still in the archives – the world’s oldest language academy redefined its mission. Gone is the prescriptive burden of defining ‘good’ or ‘beautiful’ or ‘standard’ Italian, as the Accademia now works to educate, raise awareness and encourage informed debate on language matters, in response to a radically changing social and linguistic environment within Italy and the broader context of a united Europe. The election of an Australian Italianist to the Accademia in 2016 speaks of a new openness to the Italian-speaking diaspora.

The 2020 theme, on Italian ‘tra parola e immagine’, seems ideally suited to a digital environment of comics, graphic novels and digital communication. But linguistic and figurative codes have been intertwined in Italy from the earliest writing in vernacular language. A collection of essays, entitled L'italiano tra parola e immagine. Graffiti, illustrazioni, fumetti, ed. Claudio Ciociola and Paolo D'Achille, has just been published as an e-book but also on paper. It traces a fascinating history of multimedia production and semiotic exchange over a millennium.

Words themselves have been displayed as image, from the ninth-century inscription in the catacomb of Commodilla, NON DICERE ILLE SECRITA A BBOCE, the first document transcribing the spoken vernacular, to the graffiti spray-painted on our city walls and the banners displayed (and chanted) at political rallies and sports matches. Conversely, visual representations of reality ‘speak’ to us, in Dante’s memorable definition, as visibile parlare.

Between these two poles, word and image cross-fertilise and negotiate meaning in a marvelous variety of ways. Comic strips can be dated back to the year 1080, when an Inscription in the Basilica of St Clement exploited post-Carolingian diglossia for didactic purposes. While the first-century saint speaks in “Latin”, the evil Roman Sisinnius and his servants, whom he famously addresses as “Fili de le pute”, use eleventh-century Roman vernacular.

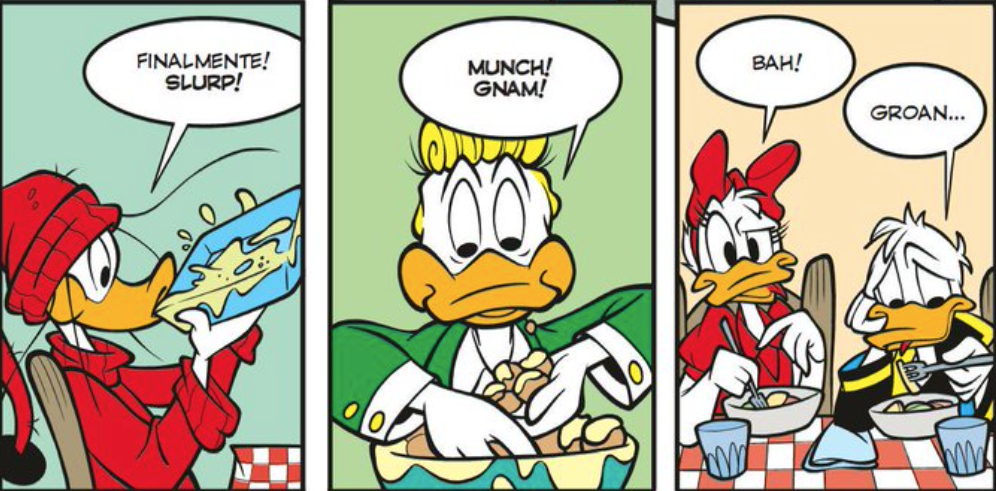

And this, nearly a millennium before Topolino taught generations of Italian children a new emotive lexicon of arcane monosyllables.

In medieval and Renaissance art, words adorned borders and frames and even entered the action to give angelic speech visible form, in Simone Martini’s Annunciation (1333).

Events celebrating Italian Language Week around Australia include webinars in Sydney and Melbourne featuring Italian cartoonists and graphic artists, a commemoration of Ennio Morricone in Adelaide, the launch of a bilingual children’s book in Perth and, from Brisbane, the 5th National Convention for Australian Teachers of Italian, via Zoom.