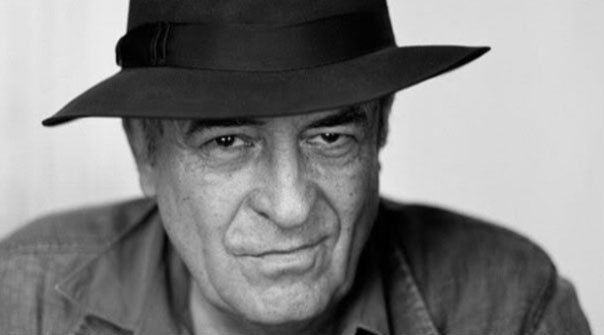

Addio Bernardo Bertolucci (1941-2018)

Addio Bernardo Bertolucci

Now, with the ranks of veteran Italian film directors already depleted to single figures, Bernardo Bertolucci, in the words of Roberto Benigni “il più grande di tutti, l’ultimo imperatore del cinema italiano”, has also left us. Undoubtedly a giant not only of Italian but of world cinema, Bertolucci succeeded, in a career that spanned six decades and produced close to 20 major films, to achieve the almost impossible feat of moving with ease between an auteurist arthouse, at times even jarringly experimental, cinema and commercially successful big-budget Hollywood-financed mass entertainment. And perhaps what especially endeared him to Italians was that he managed to achieve full citizenship of the international community of world cinema without renouncing his social and cultural roots in provincial Italy.

Born during the Second World War into a cultured middle-class family in the province of Parma, not far from the home of composer Giuseppe Verdi, Bertolucci breathed literature, opera and cinema from his earliest days. His father, the renowned poet Attilio Bertolucci, was also a film reviewer and an opera lover and regularly took Bernardo and younger brother Giuseppe with him to the cinema and the theatre. Moving with his family to Rome, the young Bernardo initially seemed inclined to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a poet, the published collection of his early poems eventually earning him the prestigious literary Premio Viareggio for a first work. But the cinema continued to rule as a parallel passion. At the age of fifteen he had been given a 16mm camera and had begun making short documentary films. Three years later his high-school graduation present was a trip to Paris where he had what he always remembered as a sort of mystical experience, provoked by days and nights of watching innumerable films at the Paris Cinémathèque. It was there that he also discovered the films of the directors of the emerging French New Wave, in particular those of Jean-Luc Godard who would thus come to exert a decisive influence on his early films. On returning to Italy he seized the opportunity to assist his father’s friend, fellow-poet and writer, Pier Paolo Pasolini in his attempt to make his first film, Accattone (1961). Making the film in the absence of any real training in filmmaking proved to be a formative experience for both of them, but it crucially also established Pasolini as the second of Bertolucci’s cinematic “fathers”, whose haunting influence he would eventually be forced to exorcise in order to affirm his own artistic autonomy. It was thus inevitable that, while demonstrating an impressive command of film language and technique, Bertolucci’s first solo feature, La commare secca (The Grim Reaper, 1962), also revealed the strong influence of both Godard and Pasolini. Two years later he began to find his own style in Prima della rivoluzione (Before The Revolution, 1964), a film still showing strong traces of Godard but set completely in Bertolucci’s native Parma and with that distinctly autobiographical dimension that would characterise his early films from then on. In spite of a warm critical response at Cannes, the film’s lack of commercial success in Italy led to the young auteur abandoning the big screen for a period in favour of making documentaries for national television.

After also working on the screenplay of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), he returned to feature filmmaking with Partner (1968), an unsettling film loosely based on a novel by Fyodor Dostoyevsky and clearly influenced by both Godard and the radical ideas of the New York Living Theatre. The film’s intentionally shrill anti-commercial ethos ensured a lack of popular appeal but both Bertolucci’s style and fortunes changed dramatically with his next feature, La strategia del ragno (The Spider’s Stratagem, 1970). Financed by RAI television, the film was conceptually challenging and openly displayed Bertolucci’s now obsessive interest in psychoanalysis but it was visually and aurally stunning. Shown twice on national television in a single week, it had already been seen by millions of viewers by the time it was shown to loud acclaim at the Venice Festival that year.

The Spider’s Stratagem thus marked a crucial turn in Bertolucci’s filmmaking, away from a cinema of ideas that spoke only to a small intellectual élite and towards finely-crafted quality films that could appeal to a mass audience. This new direction was confirmed that same year by what is still widely regarded as his most artistically accomplished film, ll conformista (The Conformist, 1970). Adapted from a novel by Alberto Moravia set in the Fascist period, the film ably mixed politics, psychoanalysis, and cinephilia in a consummate exercise of virtuosic filmmaking. The Conformist’s enormous critical and commercial success, however, was far surpassed two years later by the film that made Bertolucci’s international reputation, Ultimo tango a Parigi (Last Tango in Paris, 1972). Starring Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider in a profound study of existential alienation and sexual politics, the film won acclaim and a host of international awards, including two Oscar nominations. In an Italy still under the sway of the Vatican, however, the film quickly became embroiled in a long series of censorship battles that kept it in the courts and officially banned from Italian screens for over a decade.

In the wake of the enormous international success of Last Tango, Bertolucci was easily able to attract financing from three of the major American studios for his monumental five-and-a-half-hour historical epic, Novecento ( 1900, 1976), set and filmed in and around his native Parma. Nevertheless, in spite of its wide historical sweep and its extraordinary visual lyricism, the film was criticized from many quarters for both its ambivalent left-wing politics and its romantic approach to Italian history. It also suffered, especially in the United States, from circulating in a variety of unauthorised edited versions. Bertolucci returned to smaller-scale filmmaking with La luna ( Luna, 1979), in which he emphatically brought together two of his major interests, opera and psychoanalysis, but the film was greeted with only a tepid critical response. Two years later, La tragedia d’un uomo ridicolo (Tragedy of a Ridiculous Man, 1981), a courageous attempt to explore the issue of political terrorism which was still rife in Italy at the time, was also generally dismissed. Bertolucci’s rejoinder, after collaborating with a number of other directors on a documentary on the death of Italian Communist Party leader Enrico Berlinguer in 1984, was L’ultimo imperatore (The Last Emperor, 1987), the first of the English-language megaproductions that would characterize his mature period. The most successful film of his entire career, The Last Emperor attracted a legion of national and international awards including nine David di Donatello awards, four Golden Globes, and nine Oscars, thus elevating Bertolucci to a world superstar status unmatched by any postwar Italian director, with the possible exception of Federico Fellini . Nevertheless, while he then continued, with the help of his regular cinematographer, Vittorio Storaro , to produce films of similar extraordinary visual beauty, none of his subsequent works received the same attention or acclaim. The Sheltering Sky (1990), adapted from a novel by American writer Paul Bowles, was ironically more appreciated in Italy than in the United States, and Little Buddha (1993) received some critical praise but did poorly at the box office. For all its warmth and color, Stealing Beauty (1996) failed to impress, and Besieged (1998), the story of a relationship that develops in an apartment in Rome between a white American musician and a black African housekeeper, was also widely dismissed. A warmer critical reception greeted The Dreamers (2003), his re-evocation and patent celebration of sex, politics, and cinephilia in a Paris caught up in the turmoil of the events of 1968.

However, soon after the release of The Dreamers , a series of progressively more unsuccessful operations undertaken to relieve back pain resulted in his permanent confinement to a wheel-chair, raising the prospect of never being able to make another film. Nevertheless, and in the wake of a Golden Lion for career achievement at Venice in 2007, he did manage to direct Io e te (You and Me, 2012), the adaptation of a novel by Niccolò Ammaniti which took advantage of the story’s being largely set in an urban basement. Two years later, in a moving ceremony held on the stage of the Teatro Regio of Parma which had featured prominently in his Before The Revolution, Bertolucci was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Parma for his contribution to culture. At the ceremony he screened Scarpette Rosse (The Red Shoes, 2013) a two-minute film which he had made (and previously screened at Venice) in order to highlight the plight of the disabled in moving around Rome in a wheelchair.

Even as his health had declined, he had continued to plan his next film. Fellow veteran director, Paolo Taviani, reports that in his last conversation with Bertolucci only a few months before his death, he had recounted his preparations for a film which he would make utilising only three rooms which he could thus direct from his wheelchair. But, Taviani reports, he had stressed: “deve essere un film gioioso. Ci sarà la gioia”.