Italian Art and Politics in the New York Press

Sally Grant writes ...

Photo: Vincent Garcia

Aside from the news a few days ago that two stolen Van Gogh paintings were recovered near Naples , the New York press has covered Italy’s art and political worlds in a number of recent articles. After Virginia Raggi became the first female mayor of Rome earlier this year, Katie Parla reported on women’s status in the city in “There’s Never Been a Better Time to be a Woman in Rome” for New York Magazine. Though she notes that there are still plenty of sexist obstacles to overcome, the article emphasises a new optimism in Rome, where women are influencing city life in ever-increasing ways. Meanwhile, over at the New York Times , Rachel Donadio wrote of the tricky manoeuvring called for when art and politics collide in her account of the bureaucratic obstacles faced by—another first—the new, non-Italian, director of the Uffizi.

A German art historian, Erike Schmidt, was appointed to the role in 2015 when the Italian Culture Ministry overhauled the organisation of 20 of its most important museums and conducted an international search for new directors. Six other non-Italians were also hired in a move that is meant to vivify the running and visitor experience of these institutions.

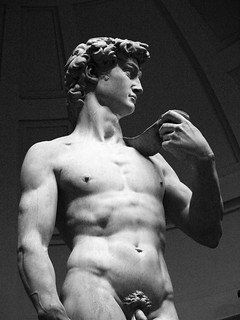

Among these institutions is another Florentine museum—the Galleria dell’Accademia—where another German scholar, Cecilie Hollberg, is the new director. In an essay for the New York Times Magazine , Sam Anderson ruminates on the Accademia’s most famous work, Michelangelo’s David , which, as the Renaissance symbol of the Florentine Republic, perfectly embodies the intersection of art and politics. Anderson ponders the statue’s cultural ambiguities (at once an artistic masterpiece and the subject of selfies and tacky simulacrums) and his own personal obsession with the sculpture. In particular, he philosophises on the weakness of David’s ankles, which was widely reported following a scientific study in 2014.

While it has long been known that there are tiny cracks in the ankles, the study revealed that if the sculpture was to tilt, caused, for example, by earth tremors, it would likely collapse. After earthquake tremors affected Florence that same year, the Culture Ministry vowed to install a protective pedestal but to date this has still not occurred. According to Anderson’s article, which was published just days before the recent devastation in central Italy, this is partly due to the restructuring of the museum and the bureaucracy and political machinations this has entailed.

Anderson does, however, also present Hollberg’s perspective on the problem, reporting that she is taking a measured approach to address the issue in the best, not just the most newsworthy, way. In this old institution there are many other problems to be addressed. Considering the meaning the David sculpture has for Anderson, this makes him uneasy, but “for now, and for the foreseeable future,” he writes, and I suspect he is talking of more than just the statue here, “we would just have to trust the David to keep standing”. After all, without such heroic works of humanity, how are we to defeat the Goliaths of the world?