Site of Resistance: The Popular Piety of Santa Maria delle Carceri in Prato

This summer I enjoyed a month-long sojourn in Florence to expand my dissertation project on Central Italian miraculous image cults established in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, specifically the cult of Santa Maria delle Carceri in Prato.

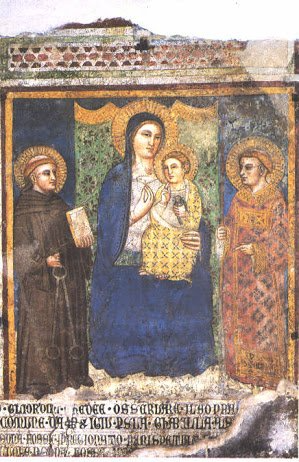

My trip got off to a promising start: I had the good fortune to attend the special Mass marking the anniversary of Santa Maria delle Carceri's first miracle. I was immediately grateful that I had arrived early to snag a seat, as the interior of Giuliano da Sangallo's church was bursting at the seams with the faithful whose eyes were fixed on the miraculous image of the Virgin and Child with Saints Leonard and Stephen (c. 1350) above the high altar. The cult's continuing significance to the diocese of Prato was immediately evident as a television cameraman ducked in and out of the tightly packed crowd to capture a perfect shot of the bishop who proudly wore a vestment bearing a screen-printed copy of the Marian image.

'Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints Leonard and Stephen' ("Santa Maria delle Carceri"),

fourteenth century, fresco, Basilica of Santa Maria delle Carceri, Prato.

However, my interest did not lie in the glow of the camera lights or in the names of the local government officials flanking the bishop. Instead, my best memory from that day was of the sacristan who, prior to the ceremony, shoved a stack of books into my arms in his excitement of discovering another person interested in his beloved Madonna delle Carceri. I was drawn to the individuals in the crowd, to the everyday people whose devotion initially ignited the cult. For that reason my dissertation focuses not on those players in the cult’s history who basked in the limelight but rather on those who remained in the shadows.

Their story begins on July 6th 1484 when a young boy was attempting to catch a cricket in a field just inside the town walls of Prato, where he suddenly witnessed the transfiguration of a fresco adorning the Commune’s abandoned prison. The image known as Santa Maria delle Carceri stood above a barred window opening onto the crumbling gaol. According to the boy, the Virgin removed herself from the wall to climb down into and clean the lower cells.[i] Following the boy’s testimony, the people of Prato and the surrounding countryside flocked to the prison to pay homage to the Virgin. Meanwhile the local government’s swift appeal to the Pope procured them sole control over the cult, and planning was soon underway for the construction of a church to enshrine the image. In 1485 Lorenzo de’ Medici managed to place his family’s stamp of possession on the popular Marian cult through his substitution of the Commune’s chosen architect with his own: Giuliano da Sangallo.[ii]While most scholars of Santa Maria delle Carceri tend to focus their energies on this Medicean intervention, my dissertation centers on the cult’s etiology which I argue was rooted in the popular piety of the oppressed members of society.

My primary documentary evidence consists of the cult’s two miracle books which contain valuable information regarding the various rituals enacted by the devotees. The first miracle book dates to 1487 and is a transcription of an earlier account by Andrea di Giuliano del Germanino, a man who sold candles at the shrine. Meanwhile, in 1505, a local magistrate, Giuliano Guizzelmi, drew from and elaborated on del Germanino’s text to compile a second compendium of miracles. [iii] According to both manuscripts, people’s ritualistic behavior was directed toward not only the original miraculous image but also its reproductions in the form of lead and paper tokens. [iv] Thus, in order to improve our understanding of the devotees’ interactions with Madonna delle Carceri’s various incarnations, my investigation considers ritual in terms of its relationship to diverse artistic media, the senses, and contemporary natural philosophical theories.

In addition to providing insight into the nature of the popular piety surrounding the Marian cult, the miracle books, together with a study Prato’s economic history, reveal the impoverishment of the cult’s original site and a large part of its devotees. Guizzelmi offers a detailed description of the prison’s crumbling ruins which are found in a field overgrown with nettles, overrun with lizards and serpents, and “open to many wicked things.” [v] Living within this rather unsavory district were Prato’s laborers, the majority of whom were poor or completely destitute. [vi] Meanwhile, the cult of Santa Maria delle Carceri attracted peasants living in other areas of the Florentine territory, the rural lands of which were crippled by severe taxation and sharecropping. [vii] Thus the original site and the cult’s initial adherents remained distanced from, and invisible to, the dominant structures of power. However, with the advent of the new cult, the city’s religious and social focus adjusted to include the periphery into the central fold as the foot traffic running through Prato’s impoverished district intensified and diversified. I therefore argue that the people employed popular piety in order to carve out a sacred space within their own neighborhood.

The upsurge of popular devotion in Prato was not an isolated case but rather part of a widespread phenomenon that began at the end of the fifteenth century, when the Tuscan and Umbrian countryside witnessed the flowering of Marian image cults. [viii] In an effort to understand Prato’s place within this larger socio-religious development, the current phase of my research is dedicated to a comparative study of these other rural cults. My summer in Italy included a lengthy road trip to visit the numerous image cults scattered throughout Central Italy. There I continued to meet devotees eager to share with me the history and traditions connected to their own miraculous images, making it evident that people’s fierce sense of ownership of, and personal identification with, their local Marian images has survived to the present day.

Notes

[i] Giuliano Guizzelmi, “I Miracoli della Madonna delle Carcere di Prato De’ Ghibellini,”in Santa Maria delle Carceri a Prato: Miracoli e devozione in un santuario toscano del Rinascimento , ed. Anna Benvenuti (Florence: Mandragora, 2005), 136–137; Claudio Cerretelli, “Da oscura prigione a tempio di luce: La costruzione di Santa Maria delle Carceri a Prato,” in Santa Maria delle Carceri a Prato: Miracoli e devozione in un santuario toscano del Rinascimento , ed. Anna Benvenuti (Florence: Mandragora, 2005), 51.

[ii] Paul Davies, “The Early History of S. Maria delle Carceri in Prato,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 54, no. 3 (September 1995): 326-329; Cerretelli, “Da oscura prigione a tempio di luce,” 51.

[iii] Isabella Gagliardi, “I miracoli della Madonna delle Carceri in due codici della Biblioteca Roncioniana di Prato,” in Santa Maria delle Carceri a Prato: Miracoli e devozione in un santuario toscano del Rinascimento , ed. Anna Benvenuti (Florence: Mandragora, 2005), 97–98.

[iv] Andrea di Giuliano del Germanino, “Cronica 1484,” in Santa Maria delle Carceri a Prato: Miracoli e devozione in un santuario toscano del Rinascimento , ed. Anna Benvenuti (Florence: Mandragora, 2005); Guizzelmi, “I Miracoli della Madonna delle Carcere.”

[v] Guizzelmi, “I Miracoli della Madonna delle Carcere,” 136.

[vi] Guido Pampaloni, “Popolazione e società nel centro e nei sobborghi,” in Prato: Storia di una città , ed. Fernand Braudel (Prato: Comune di Prato, Le Monnier, 1986), 375, 388.

[vii] According to del Germanino, all of the people of Prato and the contado answered the frequent summons of the cult’s bell, which announced either mass or the image’s transfiguration. del Germanino, “Cronica 1484,” 121–132; Guizzelmi, “I Miracoli della Madonna delle Carcere,” 137-153 ; Daniel R. Curtis, “Florence and Its Hinterlands in the Late Middle Ages: Contrasting Fortunes in the Tuscan Countryside, 1300–1500,” Journal of Medieval History 38, no. 4 (December 2012): 8–11, 15-18.

[viii] Megan Holmes, The Miraculous Image in Renaissance Florence (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 115.