‘Madonna dei Bagni … Prega per noi': a trip to Italy's maiolica heartland.

Wandering along the banchette of one of Venice's regular mercati antiquari the other day, my eye was caught by a lovely little tazza di caffé. Turning it over, I saw that it was by Ginori, and I felt a little pang that I didn't have to hand the 40 euro that the stall owner wanted for it.

Makers of fine porcelain in Doccia since its foundation by Marquis Carlo Ginori in 1735, and then in Sesto Fiorentino since 1954, and providers of employment to a substantial number of skilled workers, the firm of Richard Ginori was declared bankrupt in January of this year. After difficult negotiations, it was finally acquired by Gucci in April for 13 million euro, with plans to reinvigorate the brand, and market its wares to China in particular. The notion that hereby a Tuscan firm has been rescued by one of its own is, of course, a fiction as Gucci itself is owned by the French luxury conglomerate, Kering (formerly PPR). The fate of Ginori, swallowed up by a luxury brand giant, with all the publicity it has received in recent months, brought to mind another ceramics industry in Italy that is far older than Ginori, the impact upon which by the global financial crisis of the last few years has been just as deadly, and yet whose painful demise has gone by largely unnoticed. That industry is maiolica , and one with several links to Australia.

The tradition of maiolica , a type of pottery originating in the middle east, and brought to Italy by way of the Moors in Spain, is one that became particularly popular in Renaissance Italy. The name maiolica is applied to any Italian pottery that is highly decorated on a white tin glaze background. In the Renaissance, great value was placed on maiolica which artfully depicted scenes from antiquity, the bible, or mythology (istoriato -ware), and also on the prestigious variant of lustre-ware. The latter involves three separate firings, before the last of which the pot is decorated with metallic pigments. The final result is a film of lustrous metal over the pot, which can look remarkably like gold.

Serious fans of Renaissance maiolica find themselves inevitably consulting the work of Timothy Wilson. Wilson is curator of western art at the Ashmolean museum in Oxford, itself a great repository of Renaissance maiolica . Perhaps a more surprising, if small, repository of maiolica is the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne. Pieces in the NGV collection, some of which come from Isabella d’Este’s famous istoriato -ware dinner service, brought Timothy Wilson to Australia a few years ago in order to write a book on the NGV’s collection (Italian maiolica in the collection of the National Gallery of Victoria, 2014). I met up with Timothy again a couple of years ago in Oxford, where over lunch I happened to mention that I would shortly be travelling to Italy, together with my mother, in order to go on a maiolica hunt. My mother, a potter from Western Australia, has long had an interest in maiolica , and has lectured on the aspirations of maiolica , the ‘upwardly mobile pot.’ The energetic Timothy immediately became even more animated than usual. He took a pen and wrote down a succession of names that it was vital for us to contact. He told me to use his name shamelessly. I did. And a hidden world of Umbrian pottery opened up for my mother and me on what was to become one of my most memorable trips to Italy.

In Perugia, we were collected from our hotel by Maurizio Tittarelli Rubboli in order to go to his hometown of Gualdo Tadino. It would be hard to find a more charming and enthusiastic guide to the world of Umbrian pottery. Maurizio is a third generation maiolica potter and has established a foundation together with Marinella Caputo, with the aim of opening a museum to highlight the contribution of Gualdo Tadino to the industry (see Marinella Caputo (ed.) The Rubboli Collection. Italian Lustre Pottery in Gualdo Tadino, Perugia: Aguaplano, 2012.) Maurizio’s maternal great grandfather was Paolo Rubboli who re-introduced the art of making gold and red lustre-ware pottery to Gualdo in 1873. We were taken to see the strangely named and shaped nineteenth-century ‘muffole’ or kilns, which his ancestor had built. Although they are housed in buildings in desperate need of repair, and themselves blackened from innumerable firings (one of which is still used by Maurizio himself), Maurizio was passionate about these kilns and their place in the history of Italian ceramics. They were built according to designs outlined in the celebrated work of Cipriano Piccolpasso in 1557 and are the only ones of their kind still remaining in Italy. Maurizio also took us to see examples of Paolo Rubboli’s work in the ancient Rocca Flea in Gualdo, a building made even more imposing by the threatening clouds shrouding the mountains.

Paulo Rubboli had trained in Gubbio before returning to Gualdo, and Gubbio was next on our itinerary, where we visited the pottery of Giampietro Rampini, who, together with Sante Capannelli is the founder of ‘mastri vasai’.

We then went to Deruta where Giulio Busti, a curator and authority on maiolica showed us the town’s ceramics museum (the oldest in Italy, founded in 1898), which is housed in the former cloisters of the church of San Francesco, and which conserves more than 6000 works of pottery together with a substantial library on ceramics. But the heart of our trip, in many ways, was the visit to the Grazia Factory in the centre of Deruta. Here, what, until a few years ago, had been a bustling maiolica factory, supplying large pieces mainly to the US market (including to Tiffany, Barney’s, Saks, Niemans and others), a sad and desperate story unfolded. Ubaldo della Grazia, named after the great saint of Umbria, is the current proprietor of U. Grazia Majoliche Artistiche Artigianali, the 25 th generation of his family to head a pottery workshop that is 513 years old, in a town that has been producing maiolica officially since 1290.

Here Australian potters have been regular visitors and the factory’s museum displays the work of several of these Australians produced during their time in Deruta. The Global Financial Crisis, however, hit the Grazia business badly, and many of their standard orders have dried up. That, together with the increasing flooding of a global market with mass produced imitations has meant a reluctance on the part of consumers to buy finely crafted artisanal pots that cost many times the price. At the time of our visit, there was only a skeleton staff working at the factory, and Ubaldo had reluctantly laid off many of his other skilled workers, and spoke of the possibility of shutting down the factory.

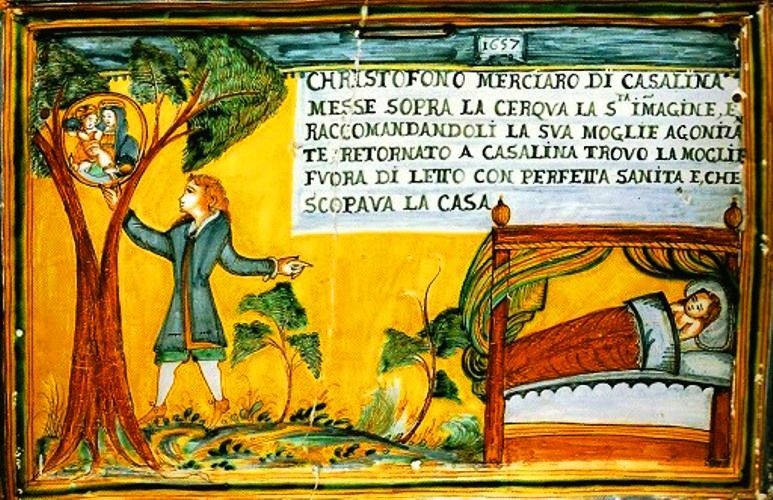

As evening began to fall, my mother and I drove up into the hillside outside Deruta where there is another pilgrimage site, not just for enthusiasts of maiolica, but for the believing faithful. A tiny sanctuary, that of the Madonna dei Bagni, sits on the hillside, in a clearing of an oak wood where numerous small springs bubble forth. In the mid seventeenth century, so the story goes, a Capuchin friar on a rambling woodland path found a shard of a cup made of maiolica depicting the virgin and child. The friar placed it carefully on a nearby oak sapling where it was subsequently found by a passing merchant, Christofano of Casalina, who nailed it to the sapling for security. The fate of the shard took on some significance when Christofano's wife became mortally ill in 1657. Rushing to the shard, Christofano prayed for a miracle. When he arrived home, miraculously, his wife was cured. And so the cult of the intercessionary power of the Madonna dei Bagni grew. An altar was built around the oak tree itself with its tiny, precious image, and a sanctuary in turn built to house the altar.

Like other locations of miraculous images in Italy, ex voti began to encroach upon the walls giving thanks for miracles received. However the roughly 700 ex voti in this sanctuary are unique as each one is depicted on a rectangle of maiolica. Every inch of the walls is, indeed, now covered with these maiolica panels depicting a series of rescues from calamity. Some of the oldest depict women and men with evil demons successfully expunged; others depict hunting accidents; boating trips gone awry; successful conclusions to difficult births, and so on. Nor is the tradition a dead one. One of the panels shows miraculous survival from a Yamaha motorcycle accident and the most recent of all gives thanks for 36 years of marriage (surely a miracle these days). The sanctuary is well tended, with fresh daisies on the altar. It was deserted when my mother and I were there, and we had this magical place to ourselves.

We left the sanctuary as darkness was settling over the hillside. I thought about those maiolica workers in the valley below – the years of training and talent now at risk, the beautiful pieces of pottery without a market – and thought of their need for a miracle.

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

- </div></li><li class="share-end"/><li class="share-reddit"><div class="reddit_button"><iframe src="https://www.reddit.com/static/button/button1.html?newwindow=true&width=120&url=https%3A%2F%2Facis.org.au%2F2013%2F10%2F20%2Fmadonna-dei-bagni-prega-per-noi%2F&title=%E2%80%98Madonna%20dei%20Bagni%20%E2%80%A6%20%20Prega%20per%20noi.%E2%80%99" height="22" width="120" scrolling="no" frameborder="0"/></div></li><li class="share-end"/></ul></div></div></div></div></div> <div id="jp-relatedposts" class="jp-relatedposts"> <h3 class="jp-relatedposts-headline"><em>Related</em></h3> </div></div> </div>